Mental Models

I recently read The Great Mental Models Volume 1: General Thinking Concepts, and took some notes along the way.

Wikipedia describes a mental model as an explanation of someone’s thought process about how something works in the real world.

The book provides an introduction to nine different models.

The Map is not the Territory

A map is a reduction or representation of reality. By definition, a representation is just that, an objective description or portrayal of something else - a belief of how we interpret something. We need to be careful when relying on maps, and remember that the belief is not reality.

When using a map, consider the following:

- Reality is the ultimate update.

- Consider the cartographer.

- Maps can influence territories.

Use maps for guidance, but not to prevent us from a new discovery, or from updating the map.

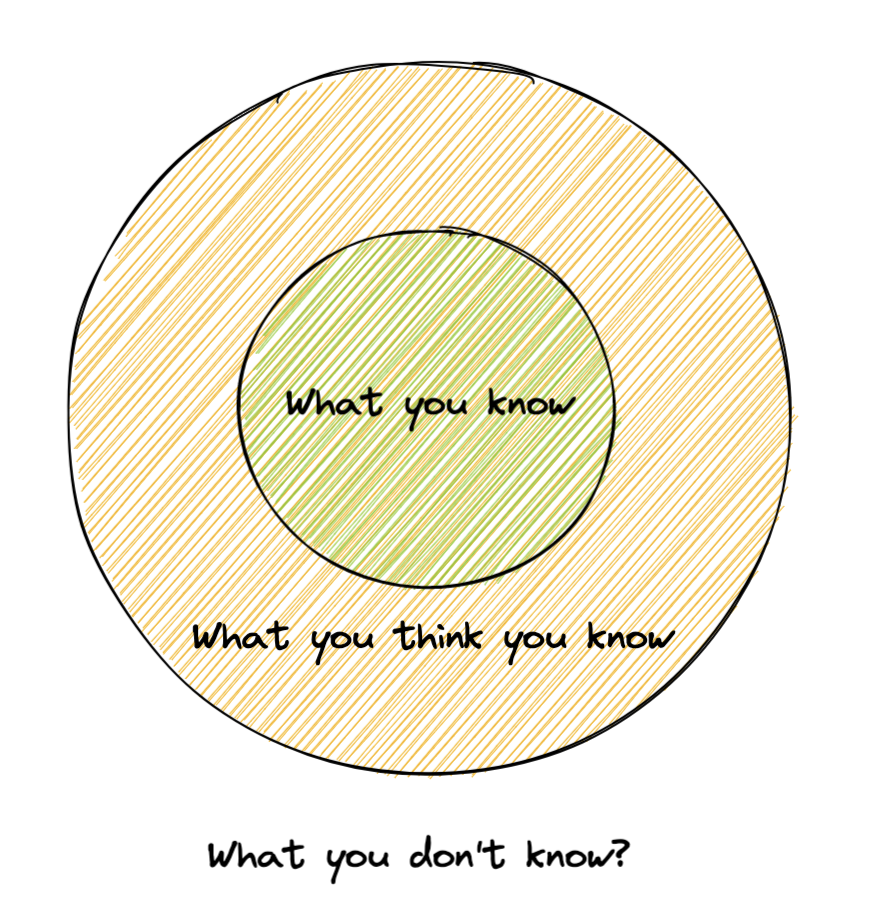

Circle of Competence

Define the boundaries of your circle of competence, and work within it. The size of the circle matters less than knowing the boundary. You can grow your circumference over time, but stay mindful of that boundary. When growing your circle of competence, or when operating beyond your circle, we should recognise that we are not experts, seek guidance or advice from somebody who’s circle of competence encompasses this area, and not be afraid to say “I don’t know”.

First Principles Thinking

Questioning the assumptions and reducing a complex problem down into blocks that are non-reducible. We want to separate facts from assumptions, and question everything. The Five whys mechanism was cited as a useful method of getting to the root of a problem. Reasoning from first principles should unlock creativity and yield novel solutions.

Thought Experiment

Using the brain’s ability to test drive various hypotheses that probe all the possibilities that we can come up with.

“What if…”

The more potential scenarios and experiments that we can test, the more likely we are to make better decisions.

The steps involved are:

- Ask a question.

- Conduct background research.

- Construct hypothesis.

- Test with (thought) experiments.

- Analyse outcomes and draw conclusions.

- Compare to the hypothesis and adjust accordingly.

Second Order Thinking

Reasoning about the potential consequences and impacts of a decision, based on the information that you have at your disposal. Second order thinking is especially useful for:

- Prioritising long term investments cover immediate gain.

- Constructing effective arguments.

Probabilistic Thinking

Estimating the likelihood, or chance, of a particular outcome.

Discusses the three aspects of 1) Bayesian thinking - taking base information into account when we are encountering something new , 2) Fat-tailed curves - the curve that extends beyond the bell curve - indicating the extremes, and 3) Asymmetries - “metaprobability”, the probability that our probability estimates are good - often not.

Inversion

Flipping the problem on its head, and working backwards from the goal. Typically we think of progressing towards an answer, but instead, it can be beneficial to start at the end, and work back from there.

The two approaches cited were:

- Start by assuming that your proof is either true or false, and step back towards what else would need to be true.

- Don’t aim for the goal/solution, but disregard what we want to avoid, and see what we are left with.

Occam’s Razor

“Anybody can make the simple complicated. Creativity is making the complicated simple.”

Prefer the simplest explanation with the fewest moving parts. Not applicable to all problems - some problems are just too complex - but where appropriate, remember that a simpler explanation is more likely to be correct.

Hanlon’s Razor

“We should not attribute to malice that which is more easily explained by stupidity”.